Bridging the Wealth Gap

Ensuring financial health in good times - and bad

By Krista Jahnke

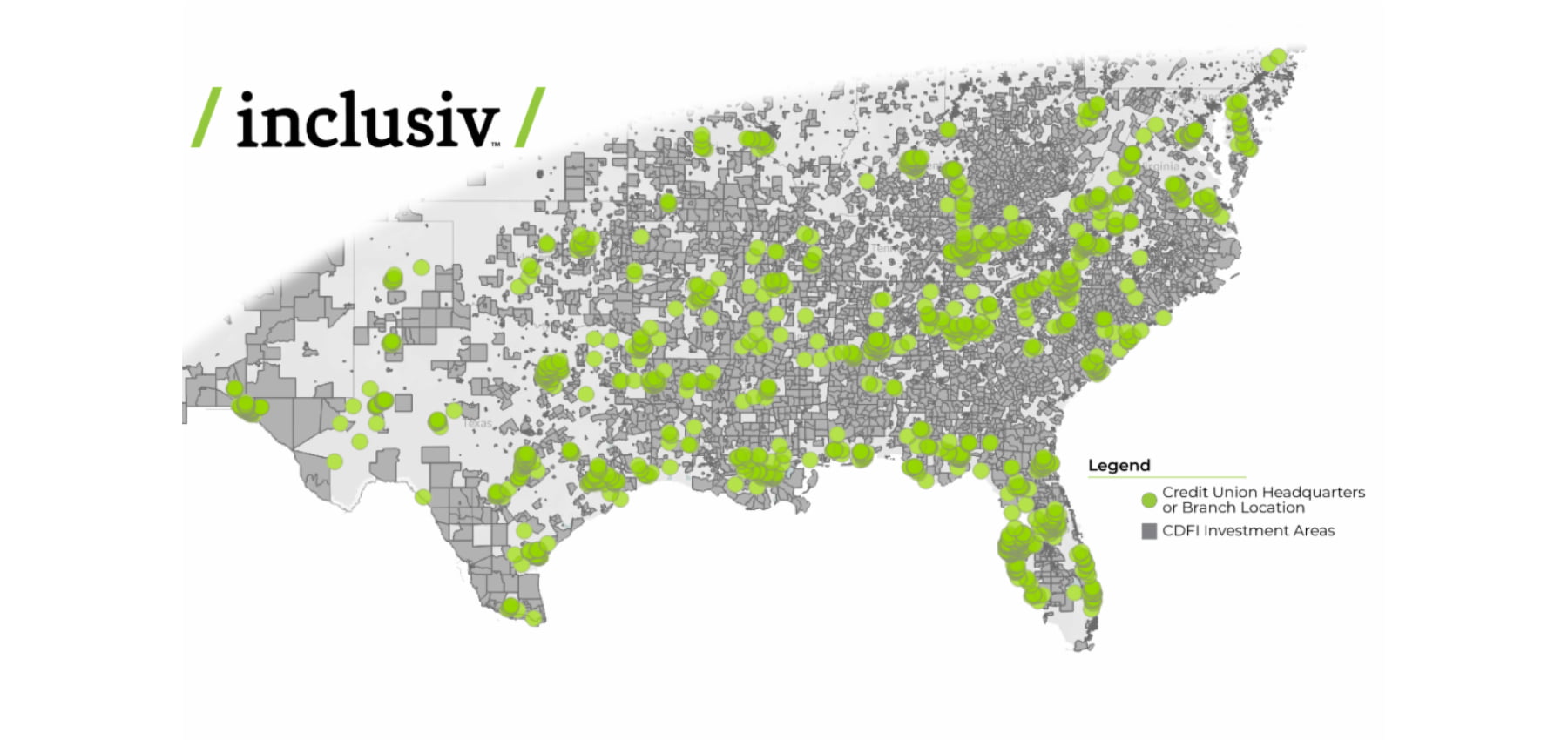

The U.S.’s gnarly wealth gap pervades communities across the country, but no more than in the South. “If you look at the map of persistent poverty areas in the United States, there are tremendous concentrations throughout the South,” says Cathie Mahon, president and CEO of Inclusiv, a partner of The Kresge Foundation. “These areas of low wealth are not evenly distributed across the map.”

Nor are they evenly distributed by race. From 1983 to 2013, the wealth of median Black and Latino households decreased by 75% and 50% respectively, while median white household wealth rose by 14%.

“We asked ourselves, ‘How do we direct resources to areas where the expansion of credit union services can have the most impact?’”— Cathie Mahon, President and CEO of Inclusiv

Students in a culinary job training program through community partner DC Central Kitchen also receive a basic savings account and 12 hours of financial management from a CDCU and Inclusiv member, Government Printing Office Federal Credit Union, located in Washington, D.C.

There are many historical and structural reasons for that gap. One is widespread predatory and exclusionary financial practices by the mainstream banking industry. Those practices include banks restricting some products and services to high-income communities, charging certain clients excessive transaction fees while limiting lending to them or selling predatory loans, Mahon says.

Because of data like this, Kresge’s Human Services Program works to advance social and economic mobility by applying a racial equity lens and addressing the wealth gap, says Joelle-Jude Fontaine, a senior program officer.

Community development credit unions (CDCUs) are one vehicle for this work. Inclusiv is a membership organization for CDCUs, which are financial institutions that provide fair and equitable loans and other financial and wealth-building services. Mahon saw a need to extend the reach of CDCUs in the South so more branches could open to take on new customers, all while doing their part to address the racial wealth gap. She needed partners.

“We asked ourselves, ‘How do we direct resources to areas where the expansion of credit union services can have the most impact?’” Mahon says. “‘How do we make change happen?’”

Secondary Is Primary

Kresge and Inclusiv partnered to address the critical capital barrier to extending the work of CDCUs — a lack of secondary capital.

Because CDCUs are typically much smaller than mainstream banks and large credit unions, they’re deemed risky by regulators and undergo more scrutiny — especially those that are minority-led. All CDCUs must maintain a minimum of 10% equity, meaning for every $1 owned, it can take $9 of deposits. By contrast, the typical commercial bank ratio is between a minimum of 4 and 8% equity. Secondary capital is one of few ways CDCUs can grow that equity. It is subordinated, longer-term debt (of at least five years) from nonmembers that regulators count as equity. It lets CDCUs grow via deposits and increase overall development activity in the form of personal loans, mortgages and small business loans.

So in 2019 and early 2020, Kresge co-developed with Inclusiv the Southern Equity Fund. Kresge contributed a $5 million equity investment, and the fund closed with nearly another $40 million, to be loaned to CDCUs across 17 Southern states via secondary capital loans.

“The fund will enable the receiving credit unions to take on an additional $300 million of deposits and serve 30,000 new members,” says Joe Evans, Kresge’s Social Investment Practice portfolio manager. “These cooperatives will in turn lend the new capital to their members, offering equitable financial products that build credit and wealth for families.”

An Inclusiv study of secondary capital tracked loans from 2010 to 2015 and found that every dollar of secondary capital was rolled over or reinvested 60 times during that period. Still, despite this impressive performance, secondary capital loans are rarer than they should be.

“That $45 million of secondary capital is going to spark tremendous economic activity,” Mahon says. “It will move us beyond proof of concept to become a vehicle by which we can start attracting more and more capital to the credit union movement from more mainstream investors. It’s scaling us to a higher level.”

Says Kresge’s Fontaine, “We see this as an opportunity to ensure greater intentionality in providing support and working with CDCUs led by people of color and committed to the economic development of these communities.”

Racial Equity: The Bottom Line

When it comes to advancing racial equity, Mahon says the fund will address it in multiple ways, but primarily through supporting CDCUs that make equitable financial services available to disinvested communities across the South—those that are disproportionately communities of color.

“They think about combining savings, affordable banking services, affordable credit availability with financial coaching, with homeownership counseling opportunities and with home mortgage loans,” Mahon says. “It’s about really rebuilding the pathways to wealth accumulation and bridging the racial wealth divide in the communities they’re serving.”

“We want to ensure the sustainability of those institutions to continue to serve the needs of their communities... And for a lot of them, growth is the right trajectory, and that’s where we’re building the capacity of those institutions to make sure that their self-determination remains and grows.”— Cathie Mahon

With grant support, Inclusiv will provide technical assistance to minority-led credit unions — especially African American organizations, which tend to be smaller, with assets under $100 million. These credit unions frequently face pressure to merge with bigger institutions, even when they provide service to high market shares of individuals in their community.

Inclusiv will work with some of these organizations to strengthen their systems and business plans and, where appropriate, work to prepare them to include secondary capital as part of their growth plans.

“We want to ensure the sustainability of those institutions to continue to serve the needs of their communities,” Mahon says. “And for a lot of them, growth is the right trajectory, and that’s where we’re building the capacity of those institutions to make sure that their self-determination remains and grows.” Finally, Inclusiv will come alongside CDCUs “to make sure that they’re constantly looking at and evaluating how their leadership reflects the communities that they’re serving,” Mahon adds.

Krista Jahnke is a senior communications officer for The Kresge Foundation.

Investing to Make Real Community Impact

Aaron Seybert, Managing Director, Social Investment Practice

Kresge’s Social Investment Practice has always sought to find ways to bend capital to support communities that need it most. And data show the communities most overlooked by traditional markets are too often communities of color.

In 2019, we made a point to find new ways to center racial equity in our work. As a team, we evaluate every deal with our approval committee against multiple criteria, including how each will address racial disparities.

That intentionality led to two investments in the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation (MHIC). A companion program-related investment loan and guarantee totaling $6 million will address the social determinants of health, which are disproportionately harmful for people of color in low-income neighborhoods in Boston. With that support, MHIC and the Conservation Law Center partnered to begin work toward investing in three health-related enterprises in 2019.

We also entered the Opportunity Zones market in 2019. We went there explicitly because we believe that without interventions and influence from mission-minded investors like Kresge, investments in these Zones will fail to provide a positive impact in Black and Brown communities. Instead, we expect the few Zones that border well-off areas, and those that include them, will see the bulk of the investment.

In response, we made two guarantee commitments, totaling $22 million, to support funds centered on providing real community impact, run by fund managers willing to agree in underwriting to monitoring and disclosing the impact of the investments.

Finally, we ventured into a state new to us — Alaska. There, we partnered with colleagues from our Arts & Culture team to invest in Cook Inlet Housing Authority. This PRI advanced racial equity by investing in Creative Placemaking-led development in one of the most impoverished and underserved neighborhoods in Anchorage: Spenard, a neighborhood composed primarily of people of color, including nearly 50% Native Alaskan.

It was a busy year — my first as managing director. My goal here is to keep moving work forward that centers equity in all its forms.