Health

Health & Housing

You can't have one without the other

By Jim McFarlin

In Sunni Hutton’s St. Louis, Missouri, neighborhood, the housing stock is more than 100 years old. And with it comes 100 years of problems.

When issues surrounding old houses are not addressed, well-documented health risks stemming from the age of the structure and neglect of its interior can flourish — lead poisoning from paint and asthma from mold, to name just two. When those issues are combined with a shortage of housing that is affordable, unjust rent practices and a history of racist housing policy, the impact is compounded when it comes to physical and mental health.

A volunteer for the national grassroots coalition Right to the City Alliance (RTTC), Hutton attended a convening of RTTC’s “Homes for All in Nashville” campaign in 2018. She returned to the Gateway City energized and better equipped to make a change in her neighborhood. In short order, she and other volunteers organized three tenant unions.

“RTTC really gave us a framework to do that — an organizing model and support in every way you can think of,” Hutton says. “We have set up a local infrastructure and are in the process of setting up fiscal sponsorship with them."

From the Community Up

Through the past decade, Kresge staff have learned important lessons about the relationship between sound housing and health. Time and again, Kresge staff have seen that solutions designed from the “community up,” arising from the participation of those most directly affected, are most likely to succeed.

“It is important that we invest in partners who help to push us forward in our thinking and sharpen our analysis about what we understand regarding equity and health,” says Kresge Health Program Officer Katie Byerly.

"Kresge is one of the few national foundations that has made some significant level of investment in base-building and power-building work that engages people in real dialogue and decision-making.”— Dawn Phillips, RTTC Executive Director

RTTC, a 2019 recipient of funding from the foundation’s Advancing Health Equity Through Housing initiative, fits that model precisely. RTTC is a national alliance of racial, economic and environmental organizations that is building a national movement for racial justice, urban justice, human rights and democracy. Foundation support enabled RTTC to expand health partnerships on behalf of Homes for All, a community-led, multi-sector movement for safe, affordable and healthy homes and neighborhoods.

“This partnership is meaningful because many national funders — certainly many national health funders — are still exploring or considering this type of investment,” says RTTC Executive Director Dawn Phillips. “Kresge is one of the few national foundations that has made some significant level of investment in base-building and power-building work that engages people in real dialogue and decision-making.”

Since its launch, Homes for All has grown to include 72 members in 43 cities representing 27 states. Unlike many groups working on housing, RTTC members are typically affiliated with community-based racial, economic or environmental justice organizations for whom housing has emerged as a priority. That national reach is exactly what David Fukuzawa, then-managing director of Kresge’s Health Program, was looking for.

“The housing crisis has spawned dozens, if not hundreds, of different local advocacy groups,” Fukuzawa says. “But they tend to represent special interests, whether it’s housing development in a specific community or advocating for specific populations such as the homeless. There hasn’t been a real national, or what you might call a trans-local, organization working for the housing community.”

Taking on the Challenges

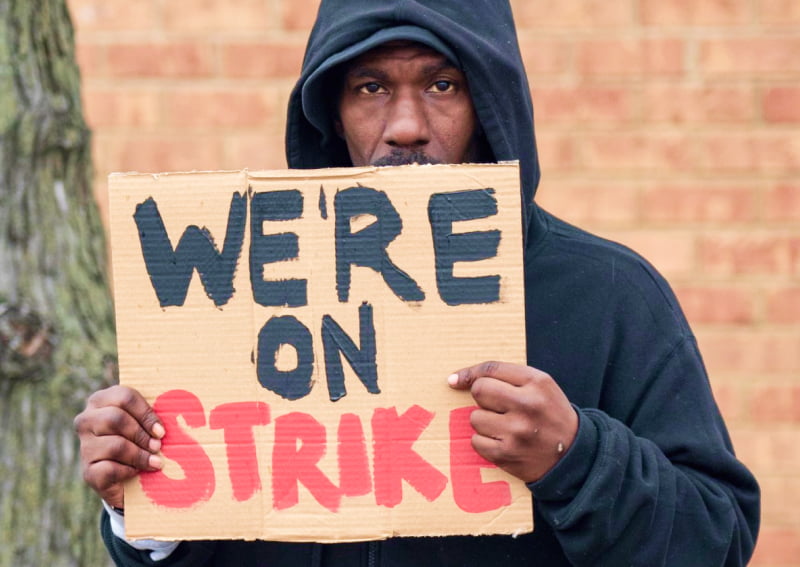

Hutton’s St. Louis neighborhood is a prime example of RTTC at work. The last semblance of tenant organizing in St. Louis occurred in 1969 when public housing renters organized a strike that helped shape federal housing legislation. It would take another five decades — and volunteers like Hutton, working with RTTC — to reestablish the importance of tenant organizing and policy change arising from the ground up.

“We know they (RTTC) are bold enough to set a vision and not let anyone push them around,” Hutton says. “We do some pretty serious work that faces opposition, especially when renters go up against corporate landlords.

“Having RTTC on our side has been huge in making sure we are prepared to take on those fights.”

Fukuzawa cites data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition stating there is no place in America where someone earning minimum wage can afford a two-bedroom apartment. In fact, he says, about 12 million severely burdened renter households pay 50% or more of their income on rent alone.

“We realized several years ago that the way housing impacts health is manifold,” Fukuzawa says. “If you get lead poisoning from a house or develop asthma, that’s pretty obvious. But there are other ways that housing can affect health, and we began to realize one of the chief ways was just housing instability itself.”

Bouncing from a parent’s house to a friend’s couch to living in your car because the landlord raised the rent 200% can take a physical and emotional toll. Multiple studies show that when housing is affordable and accessible, neighborhoods and people thrive. Children who stay in the same school do much better academically. Older adults live longer because they are more socially connected.

And according to Byerly, who has known of Phillips’ work since the foundation funded the previous organization he headed, Causa Justa::Just Cause in Oakland, California, the impact can be even broader.

“We know the house itself can be a unit of health, but the neighborhood is also,” Byerly says. “Are there sidewalks? Streetlights? Is there green space? Are there other networks within the neighborhood, helping to build that system of care we’re seeing as so important, like childcare facilities or base-building organizations? When people struggle to maintain a home … all those other pieces of stability in their lives become much more difficult. People-power is critical to tackle housing as a collective issue that is impacting population health; it’s not just an individual concern.”

“If you get lead poisoning from a house or develop asthma, that’s pretty obvious. But there are other ways that housing can affect health, and we began to realize one of the chief ways was just housing instability itself.”— David Fukuzawa, Former Managing Director, Kresge Health Program

RTTC is using Kresge funding to deepen its national health partnerships and support local members to align their vision and efforts with partners from the public health and health care sectors.

“We are also excited that a portion of the Kresge funds will be regranted and redistributed to some of these local organizations,” Phillips says. “So the funds don’t just stay at the national level, but will go back to regions and cities that are historically underserved by philanthropy.”

Byerly says that’s Kresge’s intent. “We trust Right to the City,” she says, “because they are the people doing this work on the ground every day.”

Writer Jim McFarlin is based in Champaign, Illinois.

Community-Driven Efforts Are the Way Forward

David D. Fukuzawa, Former Managing Director

It is difficult to reflect on the Health Program’s 2019 efforts to advance and center racial equity through its grantmaking and not consider the shadow cast in 2020 by a global pandemic that has affected every part of society, but especially communities of color. It is sadly no surprise to health disparities experts that a disease like COVID-19 would affect Black and Brown populations more acutely, since those with underlying conditions, such as high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity, are more likely to die from the disease or suffer more serious complications. These conditions in turn are deeply connected to segregation, lack of decent and affordable housing and healthy food options, toxic environments and exclusion from economic opportunity.

In 2019, approximately half of the Health Program’s budget supported community-led efforts to address these types of inequities. These investments demonstrated our commitment to move resources closer to communities that are seeking to build power and our ability to address challenges to well-being, health and opportunity.

These grants went to organizations such as Chicanos Por la Causa in Phoenix, Arizona, or Make the Road in New York City to support tenant organizing and expand advocacy for healthy and affordable housing; La Mujer Obrera in El Paso, Texas, or Mandela Partners in Oakland, California, coming together to build a national network to advance equitable food-oriented development; and Catalyst Miami and Environmental Health Coalition in San Diego, which are organizing for climate change mitigation and reducing their communities’ exposure to air pollution.

The Health Program has funded community-based efforts since its inception more than 11 years ago. Yet increasingly, we have recognized that policy solutions developed without the full engagement of impacted communities not only are less successful, but they also rarely confront the historic and racialized injustices that are at the root of poor health.

The way forward must include community-driven efforts back to recovery.